Treasures in Heaven Christian Mission Orphanage, Kenya

“How long has she been like this?”

“She was brought in with the last group of refugees.”

“Alone?”

“They dug her parents’ bodies out of the wreckage. She was found next to her mother. She’d already been dead for hours.”

“Poor wee bairn,” tsked the visitor, reflexively caressing the glass of the observation window to the nursery as though she could reach out and pat the skittish, solitary little girl playing with a stack of dented wooden blocks. “Pretty little thing, isn’t she?”

“Oh, I know. She’s darling. The staff loves her. Hardly makes a peep until it’s time to come back inside. Then she just drags her feet and all but twists her neck off her shoulders, staring back at the playground and looking like most of the munchkins here would if they dropped their ice cream on the ground.”

“So she just plays alone?”

“Most of the time. She prefers her own company to anyone else. Every now and again, little Japheth can get her to come out of her shell.”

“Japheth? Which laddie is he?”

“We brought him when his village’s water supply was infested with parasites. Japheth came in with the worst case of tapeworm that we’d ever seen. Malnourished, dehydrated, and he had Kwashiorkor so badly that his hair turned a strange shade of silver instead of the rusty brown we’re so accustomed to.”

“Where is he now?”

“Outside, beating all of the older children at a game of Simon Says.” The visitor gazed out the window to the courtyard and found himself grinning at a small boy of about nine, hopping on one foot and grinning when three of the urchins in the group imitated the gesture, then threw up their hands in defeat when they were called out.

“He didn’t say Simon Says,” the visitor chuckled.

“Nope. He’s good. Too good.” He was surprised that the headmistress didn’t exaggerate her claim. The boy’s wiry hair was streaked with odd, silvery tufts, despite the healthy color in his cheeks. “So how long will you be staying, Doctor MacTaggert?”

“I’ve a few more weeks left to my sabbatical.” The visitor was fresh-faced and pretty like the girl next door, but not like any girl from any of the neighborhoods she’d been frequenting for the past ten months. Her glossy brown hair was skinned back in a short ponytail that barely dusted the collar of her khaki linen tunic. Loose, white linen pants allowed air to kiss her skin and let her legs breathe in the humid climate that made her feel drenched as soon as she stepped outside. Occasionally dark, inquisitive eyes would peer back at her from the other side of the glass. Moira indulged it and repaid their cheekiness with puff-cheeked, eye-rolling looks, accompanied by sticking her thumbs in her ears and waggling her fingers. That sent more than one child running off smuggling their giggles within clenched fists, hiding gappy teeth. “I ken my fiancée will miss me if I stay much longer.” She reached back to swipe at the sweat running down her nape. The diamond solitaire caught a few minute strands of hair, ripping them loose from her tidy coif. She stifled a curse and winced at the discomfort. The headmistress peeked at the ring with a knowing glance.

“It looks like he never wanted to let you leave. It’s beautiful,” she added, nodding at the engagement band.

“I’m lucky to have him. I’m glad that he would have me,” she smiled. Lucky, she mused. Charles had walked away on what she had to offer. On what they had. The ring was a necessary ruse. She wore it like armor against the stares of prowling locals who didn’t believe that this delicate Caucasian woman was living among them on a “Doctors Without Borders” stipend. The headmistress was one of the select few who knew her credentials and pedigree before she even walked through the door. She’d received her personnel file before she was retrieved from the tiny, industrial airport and collected by a paid guide who brought her to the orphanage in a tiny Jeep that was in painful need of new shocks. Every tendon and hamstring from waist to ankle ached for weeks after that jaunting, two-hour ride.

But it had been worth it. The children were worth it.

“Kevin’s about Japheth’s age,” Moira murmured aloud, unable to help it.

“Excuse me?”

“Och! Dinnae mind me, lass. I’m just talkin’ t’meself.” She waved away her curious look. The headmistress reluctantly tore her eyes away from her, deciding that brilliant doctors like Moira were perhaps just eccentric in their ways. That could be excused if she could turn the tides of the rash of new diseases spreading through the village.

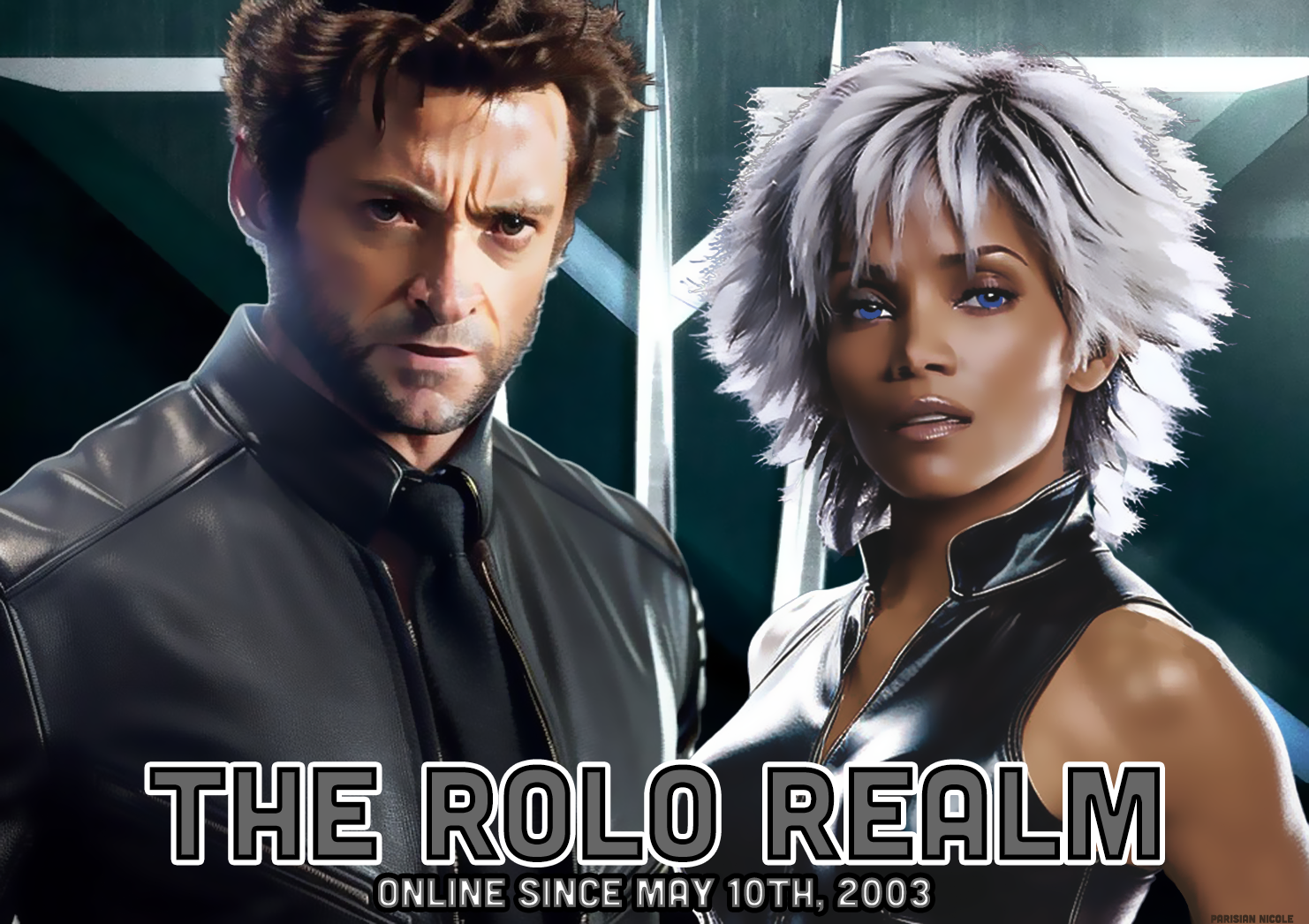

Something had to be done for Ororo, and Japheth, and all of the other children afflicted or subsequently abandoned because they were different. Cursed, some said. The headmistress stared at Ororo, watching her play fix a tea party for a random gathering of dollies at the battered wooden table. She spoke to them and pursed her little rosebud mouth around the edge of the chipped willow patterned cup and took an exaggerated pretend drink. Then, as if she felt the doctor’s stare, she turned around and leveled her with a gaze that made her tingle. Her eyes were tourmaline blue, clear, and positively ancient.

No five-year-old’s looked like that with such canny wisdom and told tales of things she should never have witnessed. This was a child, Moira thought, who has seen Judgment Day over the horizon, and shrugged with indifference. She set the cup back on its tiny saucer and folded her little hands in her lap, staring expectantly at Moira. Moira offered up a smile that she prayed held no malice.

“She’s trying to figure you out,” the headmistress suggested.

“She already has.” Ororo gave her a slow-spreading smile, then ducked her face into her thick white hair, hiding the radiant expression before it reached its full wattage. She waved back, then went back to her dollies and served another round of tea.

You must login () to review.